This is a golden age for venture capital and the startup ecosystem, as illustrated by PitchBook’s latest PitchBook NVCA-Venture Monitor. So far this year, $57.5 billion has been invested in US VC-backed companies. That’s higher than in six of the past 10 full years and is on pace to surpass $100 billion in deal value for the first time since the dot-com bubble.

Fundraising continues at breakneck speed. Unicorns are no longer rare, and deal value in companies with a $1 billion valuation or more is headed for a new record. The size of VC rounds keeps swelling. Deep-pocketed private equity players are wading in. And in San Francisco, arguably the beating heart of all things VC, the housing market is downright manic, with the median house price recently reaching $1.6 million, up from $665,000 in 2012.

Signs of success (or is it excess?) are everywhere you look. On the surface, delivering a resounding verdict that the Silicon Valley startup model not only works, it works well and should be emulated and celebrated.

But what if that’s all wrong? What if this is another mere bubble and the VC industry is in fact storing up pain, not unlike Miami mortgage brokers and small-cap tech analysts during the last two cycles? Not just for itself, but for the economy at large?

That’s the question posited by Martin Kenney and John Zysman—of the University of California, Davis, and the University of California, Berkeley, respectively—in a recent working paper titled “Unicorns, Cheshire Cats, and the New Dilemmas of Entrepreneurial Finance?”

Instead of spending millions, or billions, in the pursuit of unicorns that could emulate the “winner-takes-all” technology platform near-monopolies of Apple and Facebook and the massive capital gains that resulted, VC investors and their LP backers could instead be buying a bunch of fat Cheshire cats. Bloated by overvaluation, and likely to disappear, leaving just a smile and big losses, since many software-focused tech startups have no tangible assets.

Or in the case of bike/scooter sharing companies, the current VC flavor of the month, a parking lot of abandoned dreams.

The problem is that this cycle has been marked by easy capital and a fetishization of the early-to-middle parts of the tech startup lifecycle. Lots of incubators and accelerators. “Shark Tank” on television. “Silicon Valley” on HBO. Never before has it been this easy and cheap to start or expand a venture.

Yet on the other end of the lifecycle, exit times have lengthened, as late-series deal sizes swell, reducing the impetus to IPO (in search of public market capital) or sell before growth capital runs out.

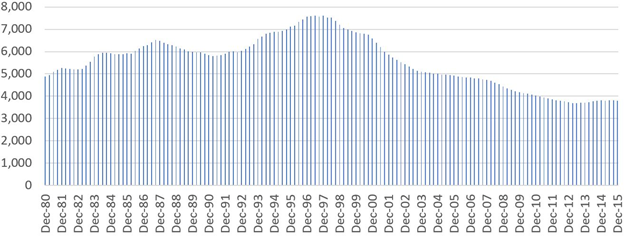

Total number of listed companies in the US by quarter

Public markets, while performing well, have been marred by still-burdensome IPO-related regulation (a point the NVCA recently made), a shift to “passive” investment strategies (and thus, a pilling in on mega-market capitalization stocks like Apple), and a lack of small- and micro-cap analyst coverage. IPO activity has been underwhelming, resulting in a steady decline of publicly traded companies.

Why is this a problem? Because, in the view of Kenney and Zysman, the VC industry lacks discipline, seeking disruption and market share dominance without a clear path to profitability. You see, VC-fueled startups aren’t held to the same standard as existing publicly traded competitors who must answer to investors worried about cash flows and operating earnings every three months. Or of past VC cycles where money was tighter, and thus, time to exit shorter.

Uber vs. Tesla

Look at Uber, the world’s most valuable VC-backed company, with an estimated valuation of $62 billion. It’s burning through cash, losing between $500 million and $1.5 billion per quarter on a run-rate basis since early 2017. Yet the company still raised a $1.25 billion Series G led by SoftBank earlier this year, according to the PitchBook Platform.

Its valuation is holding above $60 billion, a level first crossed in 2016, despite years of scandal, intensifying foreign competition and the maturation of its core business.

Compare that to the ills plaguing Tesla, which is pursuing a similar strategy of breakneck growth, burning cash to achieve scale and capture market share. Profitability is also an over-the-horizon goal. But the burdens of being publicly traded are clear, from aggressive short sellers to CEO Elon Musk’s testy post-earnings call with analysts.

Imagine VC unicorns were held to the same standard. If Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi had to publicly explain the reasoning behind its recent M&A activity in bikes and scooters (bikes from Jump, but only scooters from Lime?) or why HR woes have suddenly returned or when profitability will be achieved. Moreover, imagine what the company’s valuation would be if investors could place active bets against its success.

According to Kenney and Zysman, the uneven playing field and influx of capital into the VC ecosystem create a situation where “money-losing firms can continue operating and undercutting incumbents for far longer than previously” as their VC backers reward growth metrics with higher valuations.

“Arguably, these firms are destroying economic value. This new dynamic has social consequences, and in particular, a drive toward disruption without social benefit. Indeed, in some cases, they may be destroying social value while also devaluing labor and work in the enterprise.”

The wealth associated with the startup boom hasn’t been widely shared outside Silicon Valley and its backers—mainly institutional funds and wealthy accredited investors. Moreover, the rigor and transparency of the public markets would shed light on shady business models and practices, and ensure the common good is being served. Price discovery is a thing, instead of shopping around VC firms to get the valuation you want.

From a societal standpoint, and in the context of ongoing concerns about wealth and income inequality and corporate overreach, this is problematic. What are the positive externalities of a bunch of tech bros barreling down the sidewalk on electric scooters? Or of all the dead ICOs?

Compare that to the overreaches of the past—too many railroads, too much fiberoptic cable, too many homes. Something was left behind for consolidators to buy on the cheap and turn into a real business.

Does VC even care?

What will be left behind for the sharing-, software- and app-based businesses typifying this cycle?

The thing is, many VC investors don’t care. The rise of secondary market activity in lieu of the liquidity of an IPO, as represented by Uber’s SoftBank raise, gives early investors and insiders a way to sell their stakes at higher valuation multiples to late-stage VC or PE investors before market dominance and sustainable profitability is achieved. If it ever is.

You know, because “Greed is good.” Which you expect from East Coast cutthroats; not West Coast idealists in one of the most liberal cities in America.

The good news: The industry seems to understand the status quo isn’t healthy and, via the NVCA, is pushing policymakers to help fix it. At the risk of pushing these unicorns out to pasture—and, in some cases, to the slaughter—as overvaluations are brought back to reality.

Full link: https://pitchbook.com/news/articles/how-venture-capital-is-hurting-the-economy